MotoGP is becoming like F1! People have been saying that for years but it’s really starting to ring true.

Here’s why: In Formula One, the car makes a bigger difference than the driver. It’s true. You could be Lewis Max Schumacher and the best driver on the grid without question, but if you find yourself in the third-best car on the grid, you will not win.

Admittedly, Formula One seems a little more competitive these days, but throughout most of modern F1 history, you will notice that the finishing positions of any race mostly depict certain cars finishing together on the timesheets, and that’s because it’s down to the car more than the driver. Essentially, a Formula One driver is trying to beat his teammate to whichever position the car can finish.

That brings us neatly to MotoGP.

These days it’s more popularly known as the Ducati Cup because, right now, you really need to be on a Ducati to win. Ducati is doing brilliant work and developing the best motorcycles.

Let’s look at this from another angle. From a Formula One-type angle. The top bike is the Ducati GP 24 followed by the GP 23.

Then there’s the KTMs (after Acosta has crashed) followed closely by the Aprilia, and after that, you find the Yamahas and the Hondas.

The finishes these days work mostly in that order. It’s as though the rider doesn’t have as much say in the finishes as he used to, and that’s because it’s true.

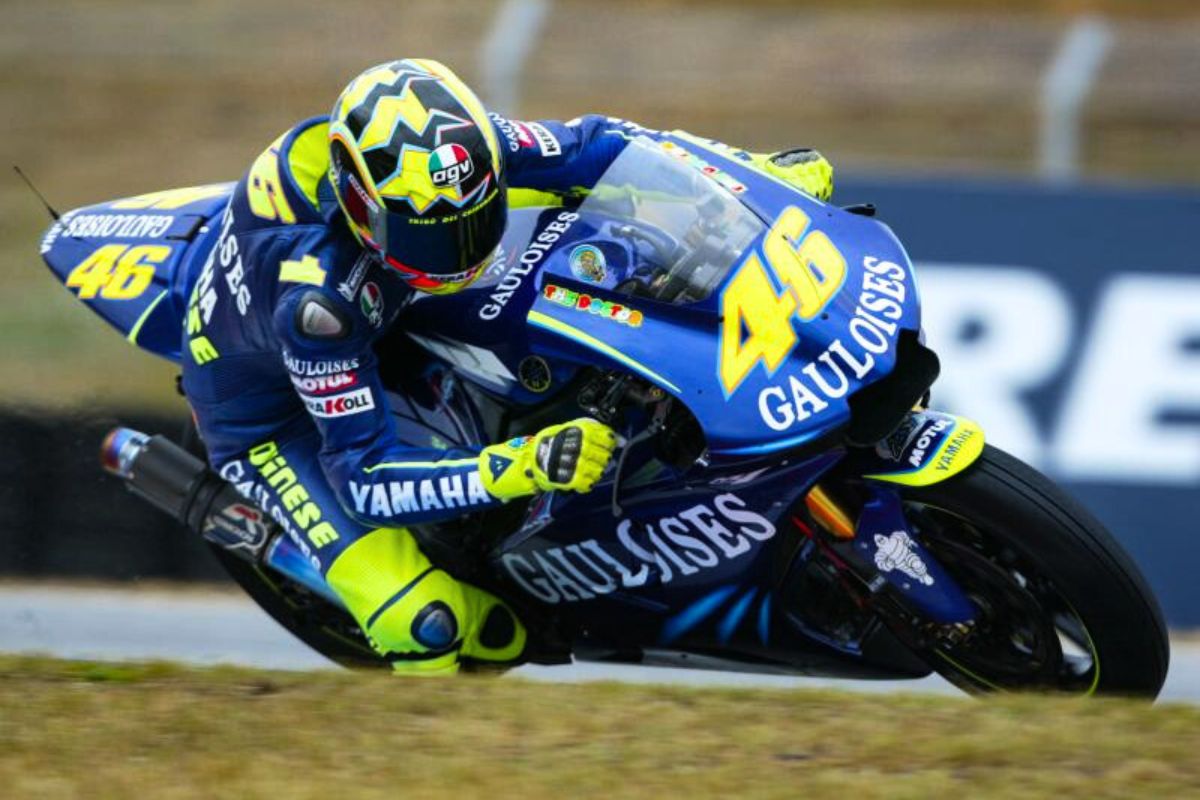

Yes, there were motorcycles that were uncompetitive in the past, but a bike that was close to the best bike could make up ground with a good rider. The most famous recent example of this was Rossi moving from his comfy winning seat at Honda and moving to Yamaha, a brand that at that stage was not even a podium contender. He famously still managed to win… his first race, and kept on winning on Yamaha’s for a long time.

Would he still be able to do that if those same riders were in these times? Probably not, and the reason is because the rider matters less nowadays than they used to.

The reason for this is down to more technology being added to the bike, because the more gadgets and bits of tech you add to a motorcycle, the less the rider matters. For example, let’s look at three technologies that have been added to MotoGP machines in the last two decades – electronics, aero and ride-height devices.

Let’s just say, hypothetically, that we have two motorcycles and riders that are exactly the same, doing exactly the same lap times. The two motorcycles have the traditional motor/chassis/tyre setup that racing motorcycles have had for decades.

Now let’s add stuff:

First, electronics control the traction control, the wheelie control and the engine braking. Then we add aerodynamic wings that affect the amount of acceleration a bike has plus its agility when turning. Lastly, we add a ride-height device that lowers the motorcycle down the straights to make it more streamlined and less wheelie-prone.

Now, let’s just say that one of our two equal motorcycles has a slightly better version of each of these devices, and each one gains that rider 0.2 sec per lap – a not unreasonable gain.

Over a lap, the bike with the better three bits will be 0.6sec a lap faster. Over the course of a 28-lap race, it will be 16.8 seconds ahead of the machine with the worst bits. Check the maths if you like.

This is where the challenge comes in, over and above the difference in gains from motor, chassis and tyres. These extra three bits add a further discrepancy, and quite a lot.

The rider on the slower bike will have to somehow find another 0.6 seconds per lap in order to keep up with the ‘better equipped’ bike. Where is this rider, who is already at the very edge of physics, going to find 0.6sec a lap?

And so herein lies the problem. The more gadgets and tech you add to the bike, the less the rider matters.

Solution?

The answer is to keep the motorcycles as simple as possible. Many might remark that these technological additions are essential to the progression of motorcycles at road level, as in what you race on Sunday, you sell on Monday. Except superbikes and sportsbikes, in general, are getting rarer, negating the need for aerodynamics that only really work above 200km/h and ride-height devices that will cause people to remove a layer of sump every time they hit a bump. The only real useful bit of tech is electronics, so maybe we can keep those.

For 2027, there are some new rules that could help ease this problem. The first is an outright banning of ride-height devices. That’s an excellent first step. Well done. The second regards the ugly wings that will have to be 50mm narrower while the front of the fairing will need to be 50mm back making it less streamlined and will channel less air onto the wings. Not bad.

The rules then get a bit bonkers… the motors will have some CCs removed going from 1000 of them to 850.

So far, these three rules are mostly designed to slow bikes down on the straights because they are getting too fast for the available run-off areas. Some might say that lengthening the run-offs might be easier, however many tracks would need to dig up their neighbour’s rose garden to do so, and that doesn’t make anyone popular.

This is all fine, except that the capacity lowering was tried before, in 2007, when they went from 990cc to 800cc. All that happened is that the bikes became revvier, more difficult to ride and it did bugger-all to lower top speeds.

And the racing was dull.

However, the MotoGP overlords have thought of this and have instead decreed that when moving to 850cc, the maximum bore allowed (the diameter of the cylinders) will be reduced from 81mm, as it is now, to 75mm. This restricts how much the bikes can rev and leaves them with enough torque to slow them down but still make them easy enough to ride…

Lets see.

So, in conclusion, the more performance gadgets added to the machine, the more difficult for the rider to make a difference. Therefore 2027 should be better than our current dilemma in 2024. We only wish it could happen sooner rather than later, preferably in 2025…. Or now!