A look at what’s what in the sometimes confusing world of road racing.

By Donovan Fourie.

Motorcycle racing can be confusing. Much of that confusion is caused by racing motorcycles inconveniently looking mostly the same. In the car world, things are a bit different – a GT car looking roughly like a two-door sports car is worlds away from a single-seater F1 car. In the world of motorcycles, many people could differentiate between the bike of Brad Binder and Johnny Rea by pointing out that one is orange and the other is green. Beyond that, from an aesthetic point of view, it’s anyone’s guess.

So let’s break it down a bit.

In tar circuit racing, there are two world championship series – the MotoGP series and World Superbikes.

Simple hey?

Well… Not really.

It gets more confusing, because beyond the MotoGP class also lies the baffling world of Moto2 and Moto3.

Then, in the WSBK series, we have the Supersport class and the Supersport 300 class. What are those? Pay attention now… There is a test later.

Let’s begin by unpacking the enigma that is MotoGP.

MotoGP is the world’s premier motorcycle racing series with more money and more eyes in it than any other form of two-wheeled racing. It’s the motorcycle equivalent of Formula One both in its premier-ness and in the fact that both are prototype series. They are both built by their respective factories purely as racing machines, only for these racing series.

In other words, we mere mortals can neither buy the car driven by Max Verstappen nor the KTM of Brad Binder.

They both contain the pinnacle of the factory’s technological level, and what is figuratively beneath the hoods remain close-guarded secrets within the factories. And we mean factories.

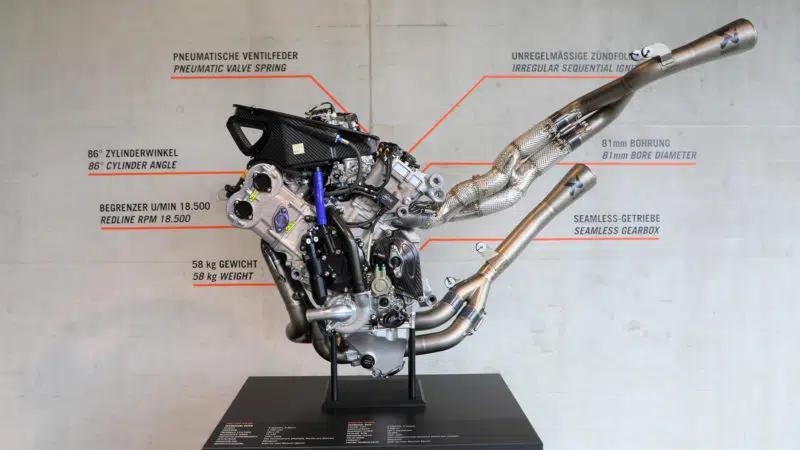

For example, in MotoGP the motors arrive in the paddock fully assembled and sealed. The pit crew working for each team take the motors as wholes and install them in the bike. At no point do those team members get to glance within the outer casing to peer into the technological marvels. Only the engineers at the factory may do so, and they sign a lot of forms that mean that their lives will be significantly more difficult should they utter a word to anyone.

The basic rules for the MotoGP class stipulate that these motors must be no more than 1000cc distributed between no more than four cylinders. While 1000cc fours are not uncommon in our mortal road-based world, these motors are clearly on another level.

The top 1000cc road-based motor manages 220hp at the crank, and that claim is somewhat generous. A MotoGP bike pushes upwards of 300hp.

Not that they manage to push that very often on account of the bikes continually wanting to flip the front wheel up and being managed by clever electronic gadgets that automatically close the throttle bodies to keep tragedy from occurring. The only time a MotoGP bike manages to go properly full throttle – even with a host of aerodynamic wings pushing the front wheel down – is when it’s in top gear, and sometimes that can be at 320 km/h.

That means that at 300 km/h, the motor is still trying to lift the front wheel and flip the bike!

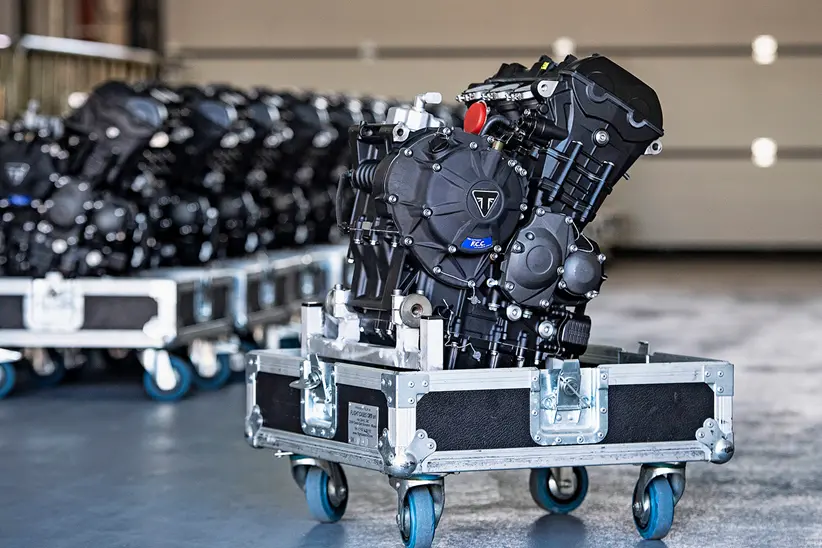

Moto2 is perhaps a little more civilised and takes a slight step away from pure prototype. The intermediate class has a one-engine rule, and from now until at least 2029, that engine is the triple-cylindered 765 from Triumph’s Street Triple. The motors are supplied to teams by Triumph and it is up to them what sort of chassis they put it into.

Mostly, they use the tried and tested chassis from German chassis builder, Kalex. Even the KTM Moto2 team abandoned building its own chassis, deciding instead to buy a chassis from Kalex and then paint it orange.

The up side to this one motor rule is that it’s far cheaper to buy motors from Triumph than build their own. Plus, everyone has the same motor and that levels the playing field somewhat.

Moto3:

Goes straight back to Prototype racing except with everything divided by four. Instead of 1000cc four-cylinder motors, the little Moto3 bikes use single-cylindered 250cc motors built by the factories and put into whatever chassis they prefer. These little packs of dynamite shoot out approximately 60hp but weigh-in at as little as 70kg. In fact, it’s not uncommon to see mechanics in the pits pick the entire bike up to move it around.

Now, let’s cross the metaphorical sea into the lands of production racing and WSBK.

Here, it gets interesting. These machines need to be based on an homologated, production road machine that anyone can buy.

These bikes either need to be 1000cc four-cylindered or 1200cc twins. There are no more twins in WSBK even though they are allowed.

Which is why we see the likes of Rea on a four-cylindered Kawasaki lining up next to the 1000cc V4 Ducati of Alvaro Bautista.

These bikes are based on road bikes, although if you were to strip them down and examine them closely, there’s little left from the bikes with flickers and numberplates. Especially in the top factory teams where these bikes are built from the ground up to be WSBK racers.

Although the rules are still there, and even if they are not exactly the same as the street bikes, the vernier of the scrutineer checking on them needs to be convinced, so while the factories can do a good deal of rule bending, they do not have carte-blanche.

The Supersport Championship started life simply as a class for 600cc fours or 750cc twins, but that class of motorcycle has fallen out of flavour among road riders in recent years, leading to a decline in manufacturers wanting to invest in the class. To make it more desirable, it now allows the likes of the 950cc Ducati Panigale V2, the 800cc MV Agusta F3 triple and the Triumph Street Triple 765, all with predetermined extra restrictions so that riders with old-school 600cc fours can still be competitive.

It’s a similar story with the 300 Supersport class where, unlike the name suggests, no one is using actual 300cc bikes. Instead, we have the likes of the KTM 390 single against the 400cc Kawasaki twin, again all with restrictions to level the playing field. In terms of the grid sizes, the 300 Supersport class has been an unprecedented success given its relatively cheap nature resulting in bursting start lines.

But how do all these classes compare with each other?

It’s complicated because the two series mostly compete on different circuits and at different times of the year, but we can attempt to draw some sort of conclusion based on the lap records from tracks on which both series compete, one of which is Aragon in Spain.

Let’s see:

MotoGP: Luca Marini – 1:47.795

WSBK: Toprak Razgatlioglu – 1: 49.375

Moto2: Sam Lowes – 1:51.730

WorldSSP: Dominque Aegerter 1:53.639

Moto3: Deniz Oncu – 1:57.896

SSP300: Marc Garcia – 2:06.263

So as is clear. Prototype has the advantage in terms of lap times, as is expected.

It doesn’t mean that production racing is not fun to watch though.

Now that you’ve looked through all of this, when someone asks at the next braai what the differences are between the bikes and the classes, you’ll be able to tell them.

Lest we forget: Electric…

The FIM Enel MotoE World Championship is the electric competition in MotoGP. The fastest electric racing motorcycles in the world enjoy eight rounds in seven countries, creating a 16-race season.

Ducati is the single manufacturer for the electric category, providing a V21L to each of the 18 riders in the nine different teams.

The MotoE has a total weight of 225Kg’s, which is 12 Kg’s less than the minimum requirement imposed by Dorna and FIM for a bike capable of completing the race distance. The MotoE is rated to maximum power and torque figures of 150 hp (110 kW) and 103 ft-lb respectively, which allowed it to reach a speed of 275kph at Mugello.